The Private Blockchain Fallacy

In all the blockchain hype, a simple, yet self-refuting idea keeps popping up: a Private Blockchain.

In order to understand why a private blockchain is nonsense, we must first define what a block chain is and what it is not. Since Nakamoto coined (PDF) the term, lets see if his description helps:

a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server to generate computational proof of the chronological order of transactions

It does highlight some important traits of “a block chain” (Nakamoto used a space between both words, I use the current popular term blockchain):

- peer-to-peer: implying distribution; at least ruling out a central authority

- computational proof: implying it to be verifiable

- timestamp-server/chronological ordering: it’s goal, but also implying permanence

Marco Iansiti and Karim R Lakhani have a more accessible explanation:

an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way.

- open (often called permissionless)

- distributed (often called decentralized)

- verifiable

- permanent (often called immutable)

In other words: anything that does not match those criteria, is by definition, not a blockchain. It may be something similar, or even something using similar techniques, but not a blockchain. This is important.

We can also look at it from the other side: if a blockchain offers these traits, when do we need a blockchain?:

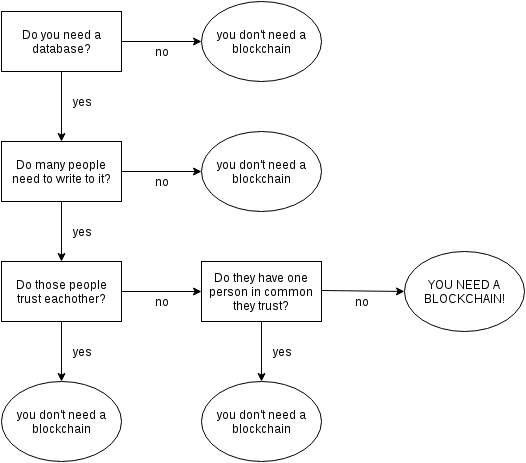

.

.

(I downloaded this image years ago and forgot to note the author. Sorry.)

This has the same treats, but turns the argument around: if your requirements don’t fit the exact things that blockchain offer: you don’t need a blockchain. In the case of a private blockchain: if it is not public, you don’t need a blockchain. We could stop here.

Reasons for wanting a private blockchain

So, why do people come up with private blockchains in the first place? We can group the arguments into three main arguments. I’ll add a fourth.

- So we can store private data or other kinds of data that should not be public. (We scrap the open and verifiable parts for privacy)

- So we can control who has read/write access (We scrap the open part for control)

- So we can scale better (We scrap the distributed part for speed).

- Because we are not yet confident enough about the security and exact traits to release on a public platform (We scrap the permanent part for flexibility)

The fourth is the only valid argument to ever use a private blockchain: as a temporary phase because you are still developing and finding out the ins- and outs of your blockchain-application: very similar to how you first release an app to your five friends and not upload it immediately to an app store.

All others reasons are pure nonsense, because they don’t need a blockchain to get the exact same outcome. Or because by definition, deploying that way, makes it not a blockchain. One could say, that by deploying a blockchain in a private environment, it stops being a blockchain.

But, there is more than just a play of words. Keep tuned.

Private data: public.

A blockchain has to be public in order to ensure permanence or immutability.

Let’s compare a blockchain to a household book. When I have such a book, in a drawer in my office, I’m the only one who can read it and change it.

So, when for some reason I bought a pair of expensive shoes, and a week later want to hide that fact, I can simply remove that line from the book. Or overwrite it with “pair of scissors”. And boom. I never bought shoes (according to the book).

But if that book is accessible amongst family members, for everyone to review, or copy, it becomes a little more “immutable”. I can still remove the “expensive shoes” line, but people might know, and family-members can call me out on it. With even more people who can access the book (why not mail a weekly copy to all family and friends?) the harder it becomes to change stuff afterwards.

A blockchain, however, has an additional trait: through applied cryptography, it allows one to easily detect when a line is changed. So all people who have a copy can detect with certainty and easily that something has been changed that should not have been changed. But this trait is only useful if other stakeholders can get copies. In a private blockchain it is really easy to change something, even when that change has a big, clearly visible effect. Simply because there is no-one to witness that clearly visible effect!

The public part, is what ensures the permanency. Not because it is impossible to change something (it is perfectly doable) but because that change, or its cryptographically effects, are seen by, other participants.

Bitcoin, for example is not permanent either, in theoretic sense. If enough participants decide that the 0.01 BTC that you paid to John a year ago, is sent to Mallory instead, that is what will happen: history will be rewritten. Bitcoins Immutability stems from the fact that anyone can detect such a change, and that a vast majority then needs to acknowledge that change.

The public part furthermore ensures that those participants will get hurt when making such a retrospective change: they have a stake in the (Bitcoin) blockchain, which will decrease in value because they just have proved that this blockchain can be retrospectively mutated.

In a blockchain, public, or private, immutability is more of an agreement amongst all participants that we won’t change history. Promised! it is not some magical “thing that comes from cryptography”. In a private blockchain that promise is easy to make. And even easier to enforce: if Mallory changes some old record, just throw him out!

With that in mind: immutability is an agreement, so you can just choose any database, even a shared excel sheet, and then promise each other never to change anything. All you need is detection that something was changed, which most database systems (or logging) will offer. You can even add some cryptography to it to make tampering more obvious or easier to revert or deal with.

Permissionless because we need control.

A blockchain has to be permissionless in order to ensure permanence.

This is very simple actually. If you can control who has access, you control who decides what the truth is. Therefore, you hold the keys to change history in any way that you want.

In the analogy of the household book, the person who controls who may write in the book and who may read from it, is, by extension, the person who controls what will get in the book and what not.

That person is, by extension, also the one in full control of rewriting the history. Because when the access-controller wants something changed, he can simply remove anyone opposing that change from write (and read) access and then promote himself (or a proxy) to be able to write. And then change it.

If other people can still read, they might notice that history is rewritten, but will lack all power to do something about it. The truth is what is in the blockchain, and they cannot change that, because of lack of permissions. It matters little how clumsy or detectable such a retrospective change is: the one with access control can, through that power, make these changes.

Immutability in a blockchain is not something magical that comes from a fancy technology . But it comes from the conditions a blockchain requires: the environment, or “world” in which it runs make it immutable.

The irony is that, actually, there is a magic technology that ensures immutability. And that technology is called blockchain. And hence has to be a public blockchain. We’ve come full-circle.

No Distribution because of scaling or speed.

A blockchain has to be distributed in order to ensure a verifiable truth.

The opposite of distribution is centralization. To follow the “household book” analogy, distribution would mean that several times a day (maybe even after every change) copies are made and exchanged amongst people. More important, however, is that none of these copies is considered “The Truth”.

If there is only ever one copy of the household book, changing stuff in there (like ripping out a page) is trivial and -if done well- undetectable.

The obvious solution would be to photocopy every page (say, daily) and keep those copies in multiple places. This is distribution. This is inefficient, slow and expensive, as opposed to having one copy and simply trusting that. But in essence what a blockchain does. Because of the exact reason of trust: so that we don’t have to trust one copyholder to tell us the truth. This is the trustless nature of a blockchain.

When all the copies at all moments can be considered the truth any difference between any copy will be detectable and should trigger an alarm. We then need a conflict resolution: which one is the truth.

In Bitcoin, they simply say: what the majority of copy-holders have is the truth. So if your book is copied amongst five people and two have in there “berkes bought expensive shoes” but three don’t, berkes did not buy expensive shoes.

If only one book is elected as The Truth, and all others are simply copies that could be used to proof that something was there at some point, that really proves nothing: who is to say the person holding the copy did not forge some records in there?

Distribution amongst all participants is crucial, because any central authority can otherwise change history at will and without detection: Verification is not possible and trust in an authority, or even a small group of authorities, is required.

To turn it around: when you don’t need that trustlessness, when you can trust a central authority, you don’t need a blockchain. To turn it around again: if it requires trust, has an authority, by nature, it is not a blockchain.

But what about my favorite coin?

If it has a “private” or “permissioned” blockchain, it is not using a blockchain. It might still be a cryptographically backed database, a solid cryptocurrency of very modern database, but it simply is not using a blockchain. And because it is not using it, it lacks one or more of the crucial traits.

Which means a single company could run away with your coins at any moment (yes, Ripple, looking at you). Or which means it is fundamentally insecure. Or it may offer very interesting solutions nonetheless.

I can probably build a very useful and interesting monetary exchange system based on trust and a Google spreadsheet. But it ain’t a blockchain. It’s “just” a spreadsheet on a Google server (with a really novel idea around it).

“You say tomato, I say tomato”

Sure. If you want to call any database a blockchain, go ahead. If you insist on calling a Google spreadsheet a blockchain: fine. Its not some protected or trademarked term. You are even allowed to call my bicycle a blockchain. It has a chain after all.

But this helps no-one. Because you are either reinventing a wheel, or you are using an extremely inefficient technology in a place where far better fitting, more efficient technologies would help you far better.

Some private blockchains are not blockchains because they are simply other technologies.

But unfortunately most private blockchains are really just inefficient, insecure or simply stupid implementations in which a public blockchain-setup is used behind closed doors. This offers none of the benefits of that public version, but all of the downsides.

Take git: git is not a blockchain; git is a DAG; so don’t call it a blockchain. A DAG is very elegant, efficient data-structure. That could even be used for distributed data-storage within a small group of participants that need some cryptographically-secure tamper-detection of their data. I’m mentioning git, because there are some cryptocurrencies that do exactly this: using a DAG to share truth amongst a private set of participants.

Or take BitTorrent: BitTorrent is not a blockchain; so don’t call it that. BitTorrent is a very neat implementation of Merkle trees, and really brilliant for distributing large amounts of data over a large amount of participants. Not a blockchain. I’m mentioning it, because this technology is often enough if you need to ensure that all participants have a copy of the data.

There are literally thousands of types of databases out there, some allow ridiculously easy syncing, others allow insane throughput, again others allow really thorough consistency checks. Or cryptographically signed logs. Or encryption of the data, or sharing of parts of data, or … I could go on. We don’t call all these “blockchains” because of a hype. They are not: They are proper solutions to a specific use-case. A blockchain is one such solution, and like most technology, it applies to a very small subset of use-cases. A private version, however, can never be such a subset.

Positive feedback, as well as images of cats, calling me names, for hating on your beloved altcoins, or other comments are very welcome at my twitter or on reddit.

This post was translated to Dutch by bitcoinspot.nl. Thanks!